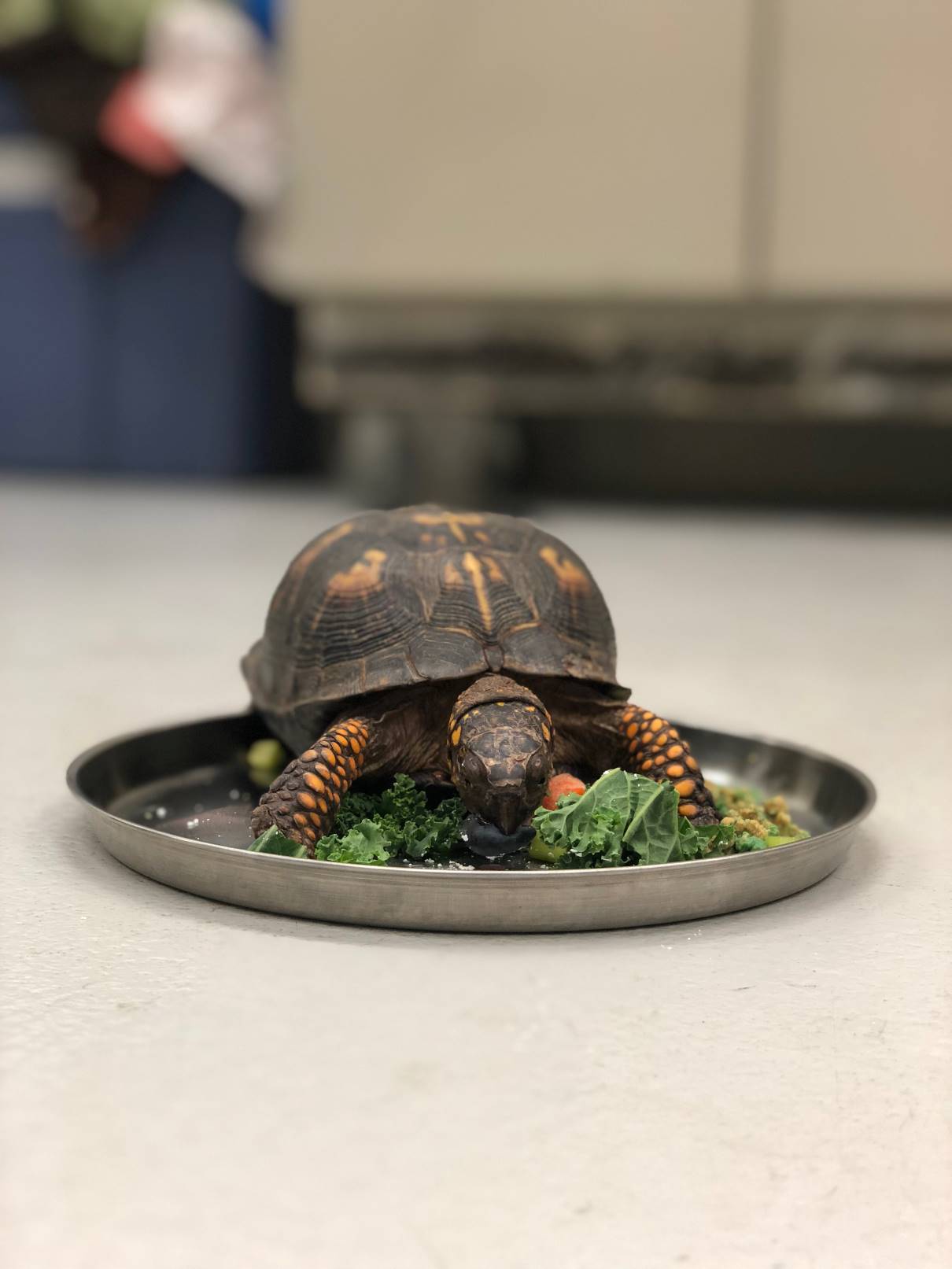

Here at the Wildlife Medical Clinic, our goal is to treat wildlife to be able to release them back into the wild. If you’ve brought in an animal and called back to get an update on it, you may have been disappointed to learn we humanely euthanized it (put to sleep). This news can be especially difficult to hear if you thought the animal’s injuries were treatable or if you didn’t think it was injured at all, but just orphaned. While an animal’s injuries and how they might be treated are the first things we evaluate when we start to examine or triage an animal, many other factors go into our decision making when we try to determine whether this animal would be able to be released in the future. To be released back into the wild, an animal must be at an appropriate age and able to survive on their own, meaning any recovery from injury must not affect their ability to hunt, forage, reproduce, or move around.

If during our exam, it is determined that the animal is not able to fully recover from its injuries, which would result in a decreased ability to survive in the wild, we will elect to humanely euthanize the animal to minimize its suffering.

Here are some of the questions we ask ourselves while triaging these animals to determine whether or not they can be treated to release.

Are these animals old enough for us to treat?

During the spring and summer, we receive many baby orphaned animals. The youngest animals may present with barely any fur or feathers and their eyes still closed. At this young of an age, these animals are normally being taken care of by mom and need to be fed every few hours, or with some birds, every 30 minutes! At the WMC, we’ve established “triage weights” for each species that allow us to determine the point at which we can effectively treat them so that they can not only survive but thrive as well. If an animal is under this weight, we will elect to humanely euthanize instead of letting the animal suffer and starve because we, as humans, are unable to keep up with its metabolic or nutritional requirements.

Will the animal be able to survive in the wild if we treat its injury?

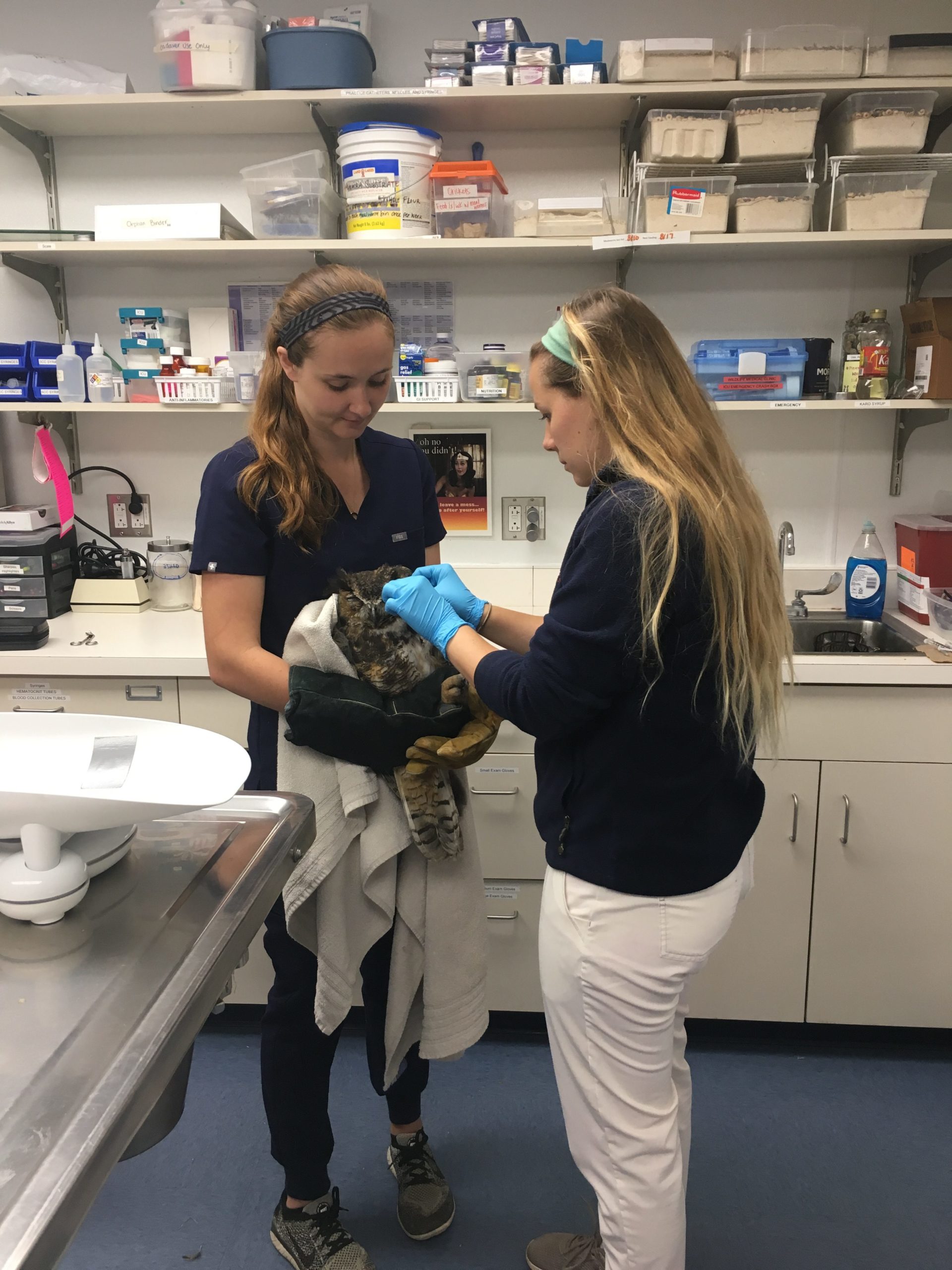

Animal species exhibit different skills and abilities in order to survive in the wild. While one type of injury may preclude an animal from being released, that same injury in another species might not be as detrimental to their fitness. Some examples we see here at the WMC are eye injuries: hawks hunt during the day by sight and heavily rely on both eyes in order to survive, whereas owls, who hunt at night mostly by sound, can afford to lose an eye if the other one has perfect function.

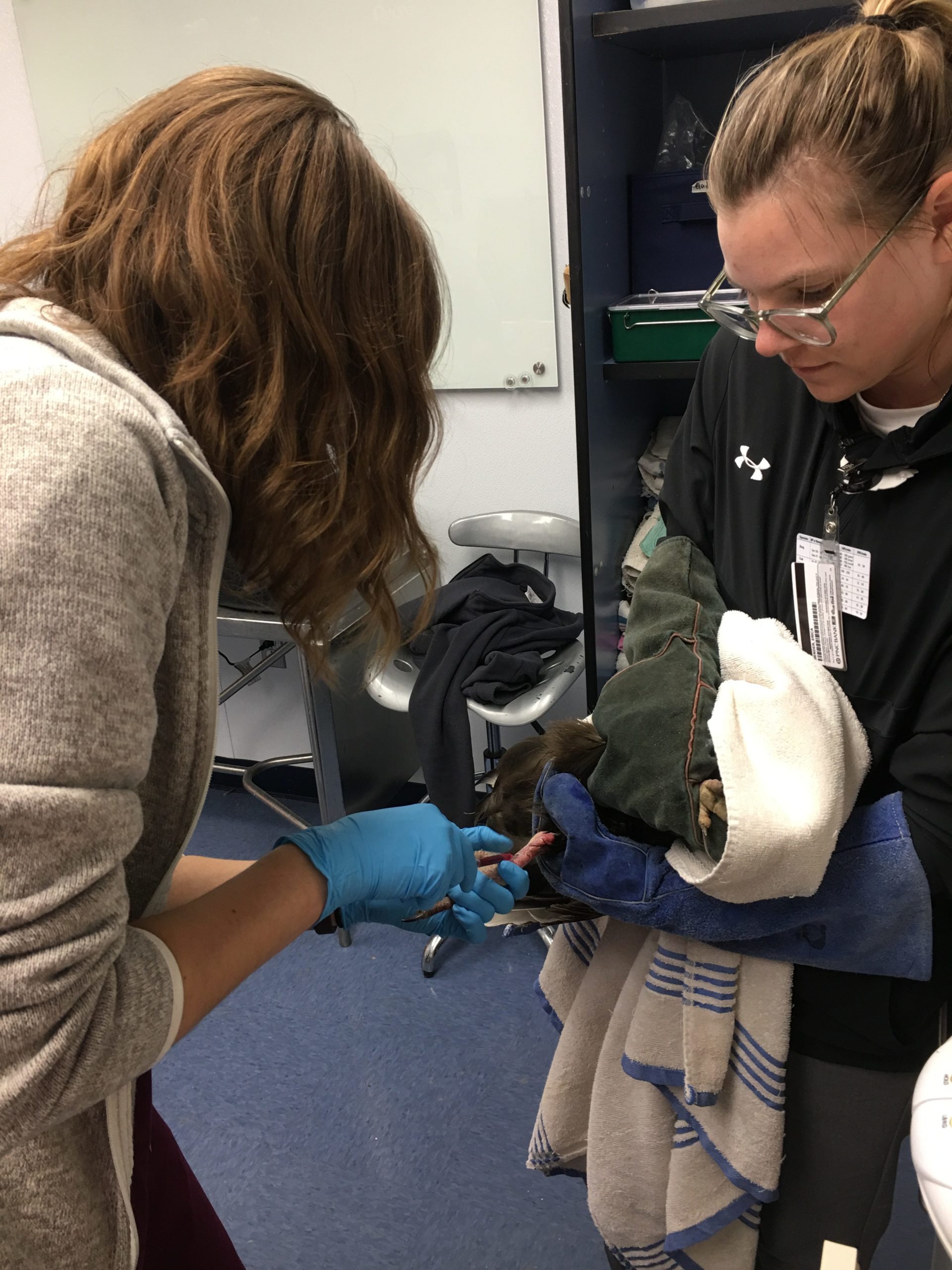

What is the extent of the injury? Will it take a long time to heal? Is it safe for us to treat?

Even if an animal comes in with what looks to a fixable injury, other factors may make it unsuitable for treatment or release. An animal who has lived its entire life outside may not react well to staying in captivity during the course of treatment. This may result in an animal exhibiting a large amount of stress, negatively impacting its ability to heal properly and resulting in aggression towards humans. Another safety concern is whether the animal exhibits symptoms of a zoonotic disease (a disease that can be passed from animals to humans). This makes it necessary for us to consider the animal’s history as well as its species’ behavior and natural history before starting any treatment.

The Wildlife Medical Clinic strives to put the health and welfare of our patients above all else. The decisions we make every day on behalf of our patients is done with the utmost care, respect, and thought to balance the animal’s medical, behavioral, and husbandry needs while the animal is in our clinic as well as its natural history and long-term prognosis. Even if a case ends in euthanasia, we are proud of the work we do, the positive impacts we can have on so many animals that would otherwise suffer without our care, and our ability to advocate for our patients.

By Erica Bender, College of Veterinary Medicine Class of 2022