Signalment and History:

Signalment and historical data are helpful for developing an accurate differential diagnosis. Many orthopedic diseases are predictable within certain age groups and breeds. Information concerning general condition of the animal (i.e., anorexia, depression or fever, limb affected, multiple limb involvement, degree of pain or lameness, duration, intensity of onset, historical trauma, effect of exercise, time of day of greatest clinical signs, effect of rest, and changes in lameness associated with weather) provide initial clues to form a differential list of potential causes. Additional questioning, physical examination, and radiographic examination will provide data to make a definitive diagnosis.

Physical Examination:

The animal’s general health should be assessed as part of the physical examination. Baseline examination includes obtaining the animal’s temperature, pulse, and respiration. The animal’s overall appearance should be noted (i.e., obesity) and thoracic auscultation and abdomen palpation performed. General health evaluation is important before anesthetizing any animal with orthopedic disease. Traumatized animals presenting for fracture evaluation should have thoracic radiographs and serial electrocardiograms performed. Evaluation of the abdominal cavity is done initially with palpation and evaluation of serum chemistry tests. Abdominocentesis and/or radiographic evaluation of the urinary tract should be performed if clinical signs suggest injury. Traumatized animals with long bone fractures frequently have concurrent soft tissue injuries (i.e., pneumothorax, traumatic myocarditis, diaphragmatic hernia, and/or ruptured bladder or urethra). It is important to diagnose these injuries before the animal is anesthetized for fracture repair.

Orthopedic Examination:

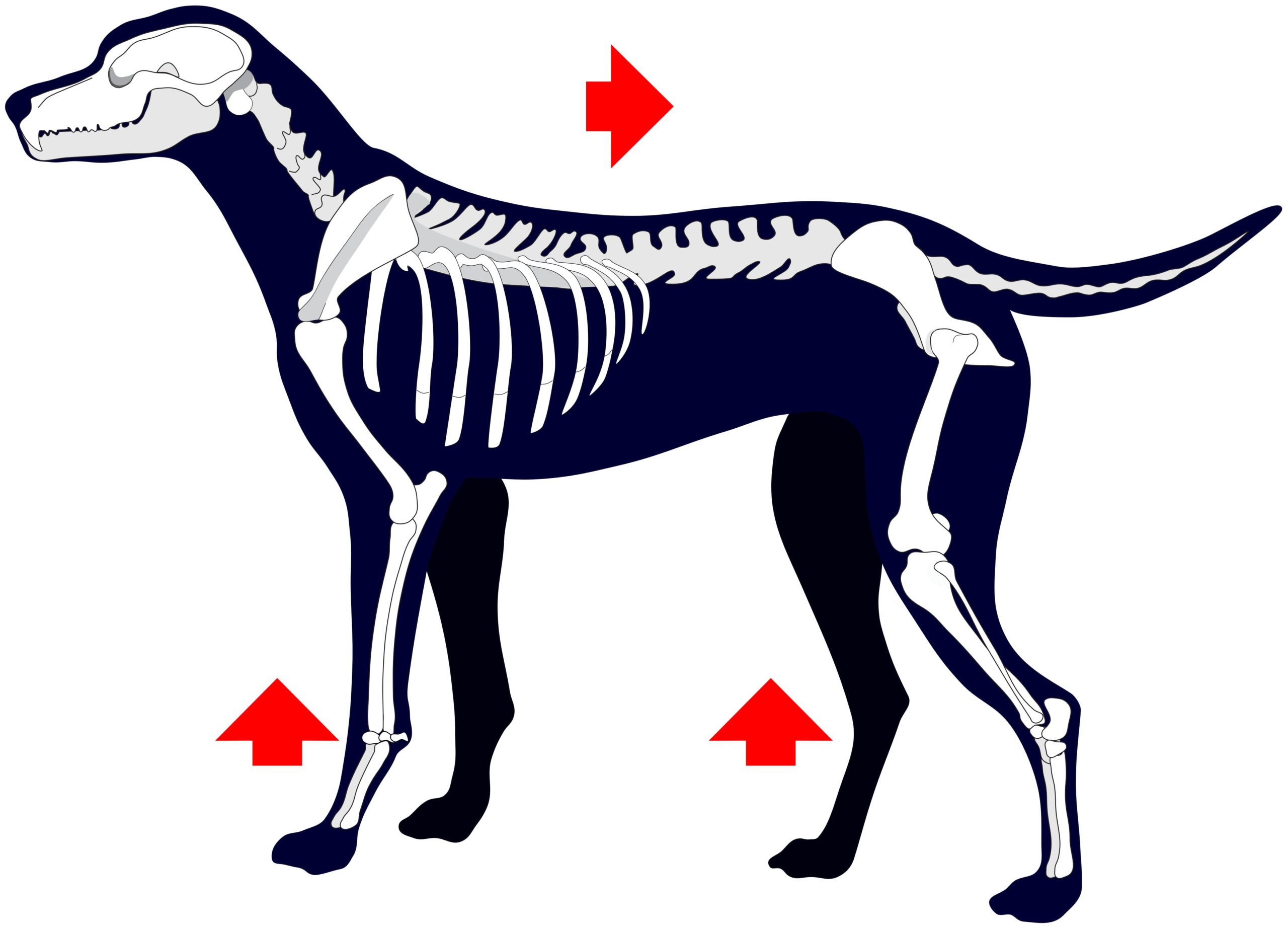

The initial examination should be done with the animal standing in order to assess muscular symmetry, joint enlargement, and proprioceptive responses. As each bone, joint, and soft tissue area is palpated asymmetry (between limbs), response to pain, swelling, abnormalities in range of motion, instability, and/or crepitation should be noted. Asymmetry should be assessed before and during individual limb palpation and can indicate tumor, abscess, atrophy, joint swelling, or greenstick fracture. Long bones should be palpated to determine if there is swelling (fracture, tumor), response to pain while firm pressure is applied (panosteitis, fracture, tumor), and/or instability or crepitation (fracture). Joints should be isolated and moved through a complete range of motion to detect crepitation, pain, or abnormalities in range of motion. Additional tests of hip and stifle instability should be performed if abnormalities are detected in these joints. Muscles and tendons should be palpated to determine if they are normal and intact.

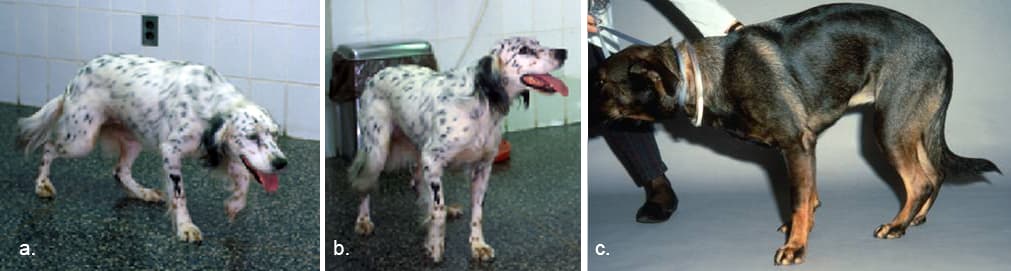

An orthopedic examination begins by observing the animal for signs of lameness while obtaining the history. This is necessary even if the owner has attributed the lameness to a particular limb, because the correct limb may NOT have been identified. The animal should be allowed to walk around the examination room and observed for obvious lameness (a.), as well as for more subtle signs such as reducing the weight placed on the affected limb when standing or sitting (b.).

Other observations may include unilateral or bilateral muscle atrophy and abnormal muscle development. Dogs with bilateral hip dysplasia or chronic cruciate ligament rupture (c.) can appear underdeveloped or weak in the rear quarters and heavily muscled in the forequarters.

Observe Dog Walking and Trotting:

If the lameness has not been localized during the initial observation, the animal should be observed while walking and trotting. It may be necessary to take dogs outside to improved footing.

To protect a sore limb animal quickly shift their weight from the affected limb, making it appear that they are landing heavily on the opposite or “good” limb. Animals with forelimb lameness will lift their heads after the lame limb strikes the ground in an attempt to remove weight from the affected limb. A short stride occurs when the animal has a decreased range of motion in a diseased joint (e.g. hip dysplasia). External swinging or paddling of the affected limb(s) occurs when the animal tries to advance a limb which cannot be adequately flexed. This is commonly observed in dogs with severe degenerative joint disease of the elbows. Animals with bilateral lameness may not limp but often show more subtle signs (i.e., shifting their weight from limb to limb while standing, shortened stride, and/or bilateral muscle atrophy).

After the lame limb has been identified, the animal should be returned to the examination room, and limb palpation and an initial neurological examination simultaneously performed. Optimally, the first examination should be done without sedation to determine the animal’s response to pain; however, this may not be possible in aggressive animals.

It is preferable to begin by examining the normal limb(s) to establish a baseline for the animal’s response.

The examiner should develop a consistent evaluation pattern. One technique is to start at the front of the animal and work toward the rear. Also, starting at the toes of each limb and progressing proximally is useful.

Now go to Front, Rearlimb, Axial Skeletal in the sequence you prefer to examine the patient. Once you identify the painful area, see Sedation and Radiographs.